Will Space Stay a New Frontier? - David Southwood

|

Professor David Southwood was appointed

Director of Science and Robotic Exploration of the European Space Agency (ESA) in April 2008, having

previously been Director of Science. After graduating in 1966, he worked at Imperial College London and UCLA.

Professor Southwood joined ESA as Head of Earth Observation Strategy in 1997, where he introduced a new

programme in Earth science, called 'The Living Planet'. In 1999 he returned to academia to become

Regents Professor, first at UCLA and then at Imperial College. In May 2001 he was invited back to ESA to

lead the Space Science programme. Professor Southwood is credited with more than 200 publications and

scientific articles, and has worked on a variety of space missions including the NASA/ESA/ASI Cassini-Huygens

mission, now orbiting Saturn.

The Directorate of Science and Robotic Exploration is devoted to the mandatory scientific programme and to the part of exploration dedicated to robotic exploration, and was created in April 2008 in an organisational change triggered by ESA Director General Jean-Jacques Dordain and endorsed by the ESA Council. David Southwood is also a keen reader of science fiction. His interests were combined when he appeared as a Special Guest at Interaction, the 2005 World Science Fiction Convention in Glasgow. This piece was written specially for Renovation.

|

|

Some thoughts from David Southwood, Director of Science and Robotic Exploration, European Space Agency, Paris, France.

All fiction requires some suspension of belief. In an age where technical advance has been so fast, a form of fiction based on the suspension of, small adjustments to, or even just extrapolation of current science and technology, i.e. science fiction, was always going to find an audience. Moreover the link between science fiction and the age of space exploration was even more direct as the dawn of the space age as well as opening actual new physical frontiers was inevitably going to open new frontiers in the mind as well.

On the eve of a Worldcon devoted to "The New Frontiers", it therefore seems reasonable to ask where space exploration is going in the next fifty years. Indeed, if the past fifty years have seen science fiction, technological advance and the development of space exploration linked, one can even ask, more aggressively, if space can hold its position as a new frontier for the human mind for the fifty years to come.

There have been disappointments in the past. Fifty or even forty years ago, I would have expected colonies on the Moon by now. It has not happened. On the other hand, when I was a student in the sixties, who dreamed that we would regard the black hole as an observational reality rather than a theoretical construct? Even more remarkable, until twenty years ago, who would have dreamed that by now we would know of more than 400 planets outside our solar system?

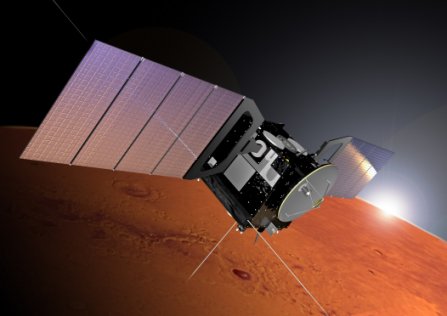

What then are the prospects? Close to home, Mars has to be the number one target. I find it hard to look at Martian images without pondering the similarity to Earth - and yet the dissimilarities are also evident to any Earthling. The priority on Mars brings in a personal note here. My colleagues in ESA along with my NASA counterpart, Ed Weiler, and his colleagues have worked in recent years to create a frame for a joint long-term exploration of Mars by Europe and the USA. All looks to be in place now. In time NASA and ESA should be joined by partners across the world. We are about as set as we can be globally for a long-term exploration of Mars.

50 years from now, we should expect to have explored Mars almost as thoroughly as the Europeans of Verne's or Wells' age had explored Africa. If so, we should have a solid grasp of the history of Mars as a planet and of whether past, present or future life could be supported. The effort to get there is going to be fun for all involved and I hope it will inspiring for everybody.

I admit I had never thought about it before, and it depends a bit on what the answers are, but could giving the creative minds of scientists the means to uncover the mysteries of Mars mean removing Mars from the imagination of future creative writers of science fiction? I leave that to be pondered.

One can seriously imagine humans living on the surface of Mars in 2060. But then perhaps not; fifty years ago I imagined there would lunar colonies by now. What seems clear is that Mars and the Moon remain the only places where one can possibly envisage any sustained human presence apart from space stations. And yet there is so much more of the universe, beyond the Moon, Mars and indeed the solar system.

In fact, how fast we proceed in such explorations may depend also on technological leaps. The outer solar system calls for radioactive heat sources and power supplies. One step beyond is to develop nuclear engines, for example, nuclear electric propulsion. These could revolutionise our capabilities in the outer solar system. However, it is hard to imagine any serious effort towards sustaining human activity on Mars without such systems, as well as heavy lift vehicles. The availability of either would enormously change prospects at the same time for deep space robotic exploration. It could be that deep space robots would effectively surf in the wake of a grand effort to put people on Mars.

Perhaps the biggest scientific beneficiaries of space have been the astronomers, although they do not always admit it. It is a pretty safe bet that our understanding of the universe beyond our solar system will have advanced enormously by 2060. What might be the big conceptual breakthroughs? At present, the identification of extra-solar Earths would appear the most tantalizing. However it is almost certain that we will have a entirely new gravitational wave astronomy by then and who knows what looking at the universe through gravity might bring?

(Cosmic Microwave Background mission)

In practice, I am confident that space will still loom large in setting technological agendas that will spark a response in the creators of science fiction. Perhaps my great confidence in this is not based in any specific prediction of what may be done, so much as my feeling that increasingly our society functions around humans using more and more able machines, from our smart cards to Blackberries, from communication media that provide what we want when we want it to cars that talk to us, tell us when they are sick and which way to turn. The evolution of human-machine interfaces will change our society and, probably, us. Inevitably space is going to remain difficult to access, a place difficult to do things and inevitably this is one frontier where machines, scientists and engineers are going to remain working together.

(c) Professor David Southwood, 2010.

Artwork: All Images from ESA.